Is Singapore ready for the open electricity market?

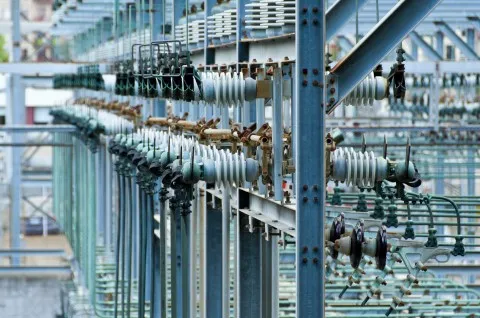

Operational doubts persist as power operators look for more physical space.

When Singapore held the soft launch of the Open Electricity Market (OEM) in Jurong, it enabled households and firms to buy electricity from their chosen retailers. OEM is expected to be rolled out to the rest of the country from the fourth quarter of 21518, but programme implementation has seen its share of challenges.

In April, Soh Sai Bor, assistant chief executive of the Singapore Energy Market Authority’s economic regulation division, said the agency has banned door-to-door sales or marketing activities at or near residential premises in order to protect consumers from aggressive marketing tactics. "We will not hesitate to act against retailers if they engage in dishonest marketing practices," he said, in response to a public letter claiming the EMA had adopted a "hands-off approach" towards the OEM as retailers begin to jockey for a slice of the market.

"Some retailers have resorted to gimmicks, like free electricity and cash rebates. This may not benefit customers in the long run, and serve to confuse and encourage wasteful habits. In addition, the retailer who gets the most business may not be the cheapest or the most eco-friendly; just the one with the most marketing savvy," the public letter read.

The OEM hiccups — when taken together with what analysts have cited as larger uncertainties surrounding the country’s focus on large-scale solar systems despite the lack of physical space and the long-term impact of the looming carbon tax scheme — serve to illustrate Singapore’s growing pains in its drive to become a renewables leader in Southeast Asia.

“With the OEM to be implemented across Singapore by the end of this year, solar power developers will be able to tap the residential consumer market to offer green electricity. After 2020, the pace of installation is expected to be even faster; given the target to reach 1 GW capacity 'beyond 2020,'" said Gautam Jindal, research associate at the Energy Studies Institute in the National University of Singapore (NUS).

The OEM is one of the key projects meant to propel solar power development in Singapore and enable the country to meet its target of 350 MW installed capacity, and it has a lot more ground to cover. "Singapore has two years remaining to reach its target,” said Jindal. “As of the first quarter of 2018, less than half of the target has been accomplished.”

However, Jindal noted that the SolarNova programme has already awarded three tenders for a combined 190 MW PV capacity, and will come out with a fourth tender in 2019. The third tender was awarded in June to Sembcorp Solar Singapore, a subsidiary of Sembcorp Industries, which entails building, owning, operating and maintaining rooftop solar systems across 848 apartment blocks and 27 government sites.

The project involves a total capacity of 50 MW and covers blocks in the West Coast and Choa Chu Kang town councils. The Housing and Development Board (HDB), which runs the programme with the Economic Development Board (EDB), said the tender was also the largest so far under the SolarNova programme. Sembcorp Solar Singapore expects the construction of the rooftop solar systems to start in the third quarter of 2018 and aims to complete it by the second quarter of 2020.

As of the first quarter of 2018, the number of grid-connected solar PV installations in the country stood at 2,155, almost double from 1,138 in the year-ago period, EMA data showed. Of these, 734 or one-third were residential installations, up from 374 in the prior year, and the rest were non-residential.

Still, Zhi Xin Chong, associate director of PGCR Research at IHS Markit, reckons Singapore’s ability to deploy large-scale solar systems will be constrained by the lack of space. “I think the concept of Singapore moving largely to renewables is wishful thinking. But Singapore can contribute to other parts of the renewable ecosystem.”

Chong said Singapore is the financial hub for Asia and renewable energy developments in the region requiring capital raising, legal structuring, urban planning, efficient management of utility infrastructure, all of which are expertise that can be found in Singapore. “Whilst we are unable to physically develop renewables in a large way in Singapore, we can assist in the developments in the region," he noted.

In July, Singapore’s Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli announced that the country would launch a Climate Action Package, which aims to develop capacity in the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations. The capacity-building programme will cover disaster risk reduction, climate science, climate finance, flood management, and long-term mitigation strategies.

Sufficient emissions target?

Singapore’s level of commitment to reduce emissions have also come under scrutiny, even as some analysts have defended it remains appropriate given the country’s geographical constraints and integrated industries.

Earlier in April, The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) said that Singapore is “well placed” to reach its commitment under the Paris Accord to lower its greenhouse gas emissions by 36% per unit of GDP by 2030 compared with the 2005 level as well as stabilise them in absolute terms by around that year. The assessment cited long-term plans to promote efficient energy use and the passage of a Carbon Pricing Bill, the latter likely to “go a long way” towards creating industrial incentives in clean energy.

On the other hand, the Climate Action Tracker -- a consortium of research organisations tracking climate change action -- has criticised Singapore’s commitment to lower emissions as “highly insufficient” given the country’s high economic capacity. “Whilst it has considerably expanded its renewable energy capacity, Singapore’s main focus for climate mitigation is now on energy efficiency programmes. However, this will not compensate for the increasing energy demand from the industry and buildings sectors, which will result in rising emissions,” said CAT, expecting its reduction target to lead to emissions in 2030 rising 123% above 1994 levels.

However, Jindal said that Singapore’s targets for emissions and renewables are “sufficient given its national circumstances,” noting that the country has already shifted 98% of its electricity to natural gas, the cleanest possible fossil fuel, and waste incineration. “[Singapore] has limited technical potential for most renewable energy sources and solar PV is constrained by land scarcity and intermittency concerns,” he said, adding that the country’s main industries, such as petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals, are highly integrated. “It’s difficult to introduce energy efficiency measures that may alter tried and tested processes.”

Carbon tax conundrum

In February, the Singapore government announced that heavy emitters in the country will be charged $5 per tonne of greenhouse gas emissions under its carbon tax scheme to be implemented in 2019, reduced from the previously announced range of between $10 to $20 to allow companies more time to adjust and initiate energy efficiency projects.

Facilities that produce more than 25,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions or more annually, which is equivalent of emissions produced by the annual electricity consumption of 12,500 HDB four-room households, will have to pay the carbon tax.

"With Singapore set to impose a carbon tax of $5 per tonne of CO2 emissions on large polluters including power generators, it will be interesting to see how the situation unfolds,” said Jindal. “All but one of the generation companies made losses in 2017; and whilst the carbon tax is meant to be passed down to the consumer, generators and their retail arms may look to absorb the costs in order to maintain their market share.”

Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat has argued that the carbon tax will push businesses to take measures to reduce carbon emissions, noting that large emitters account for about 80% of Singapore’s emissions. He said these government measures, including a budget of more than $1b in the first five years to support projects that reduce emissions, will push companies to become more competitive.

Still, large emitters have pushed back at the proposed carbon tax, viewing it as an additional burden that would lower their global competitiveness. Some firms have also asked for the carbon tax to be based on emissions performance benchmarks rather than a flat rate, claiming that it will result to a fairer system.

Despite these concerns, Heng has insisted that a credits-based carbon tax system is the “economically efficient way to maintain a transparent, fair and consistent carbon price across the economy to incentivise emissions reduction.” The Singapore government said that by 2023, the carbon tax rate will be reviewed and is envisioned to be raised to $10 and $15 per tonne by 2030.

"Singapore is trying to contribute and do its part to reduce carbon emissions. It has established the NCCS that has been pushing a number of initiatives, most recently, the proposed carbon price. Singapore’s renewable targets are aspirational but there has also been a drive from the government to realise this. Such as HDB deploying solar systems on its rooftops or PUB piloting a floating solar farm in Tengah reservoir," said Chong.

In October 2016, the Singapore government launched the floating Tengah test bed, the world's largest. Then in April, PUB called a tender to conduct engineering studies for the deployment of a 1 MWp floating solar PV system at Lower Seletar Reservoir and a 1.5MWp floating solar PV system at Bedok Reservoir.

Both systems will help power the national water agency’s operations and are estimated to cut down its carbon footprint by about 1.3kt CO2 annually, similar to removing about 270 cars off the road per year.

![Cross Domain [Manu + SBR + ABF + ABR + FMCG + HBR + ]](https://cmg-qa.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/exclusive_featured_article/public/2025-01/earth-3537401_1920_4.jpg.webp?itok=WaRpTJwE)

![Cross Domain [SBR + ABR]](https://cmg-qa.s3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/styles/exclusive_featured_article/public/2025-01/pexels-jahoo-867092-2_1.jpg.webp?itok=o7MUL1oO)

Advertise

Advertise